This past month, I finally finished Final Fantasy X, meaning that within the last 365 days, I’ve completed Final Fantasy VII, VIII, IX and X. While I played them a bit out of order (9, 7, 8, then 10), playing them all in close succession has inevitably made me look more closely at both how the series evolved and introduced, tweaked and removed different mechanics in the four years between VII and X’s releases.

Even more than that, it has helped me understand what I like out of these games and JRPGs on a broader scale, especially on the mechanical side. So from the base battle mechanics to character roles, limit breaks to summons, here is an analysis of the first four Final Fantasy games of the PlayStation era, or “Why Final Fantasy X’s battle system is miles ahead of its predecessors.”

Active Time Battle vs. Traditional Turn-Based Battle Systems

Before I begin, I believe it’s important to note that my opinion of which battle system is the most enjoyable and best implemented in these four titles is heavily biased towards the one game that decided not to use the Active Time Battle first introduced way back in Final Fantasy IV.

In Active Time Battle, characters have an action meter that fills up at a certain rate based on their speed and once that bar is full, it allows the player to select an action for them. In that way, it directly simulates the Set Turn order experience, but enemies will not wait on the player’s choice to attack, meaning the player has to be on their feet to make decisions and correct moves in certain moments or risk dying to a string of party-killing attacks.

The system attempts to bridge the gap between real time action combat and classic turn-based combat. I don’t believe it does this well, and as a player, I would not prefer ATB to the two other systems it’s trying to bridge.

Not being able to choose an action until the ATB gauge fills means that you’re often wasting more time choosing an option than waiting for the gauge to fill, which means the player will always be at a disadvantage to the computer’s instant decision-making. This means that the skills you’re improving aren’t as much making quick decisions as much as how quickly you can navigate menus.

The game can fudge this, of course. Enemies can be programmed to take longer to move to account for the time difference expected of the average player, and time can even be paused while the player is selecting a move. For the prior, though, it’s hard to gauge what “average” even is, and would invariable leave certain players out in the cold. For the latter, well, at that point, why not just use a Set Turn Order system instead?

Which brings me back to Final Fantasy X, which eschewed the ATB system from the previous 6 games for a more classic Set Turn Order system that not only iterated on how the classic systems function, but took aspects of ATB to do it.

Final Fantasy X took a freestyle approach to its turn-based order. Instead of set turns where every unit is able to make an action per round, FFX sets every unit up on a timeline, with set intervals between unit actions based on their speed. The distance between character’s speeds are even shown in this timeline, meaning spells that had been used in the ATB system to speed up or slow down the gauge like Haste and Slow were easily able to return and effect battles in the same way: giving the player or enemies more or less actions. Small tricks like changing weapons could even delay a character’s turn momentarily, even if you’re changing to the same weapon, letting the player choose which order they wanted their units to move in.

A Puzzle-Like Battle System

That last part also plays into the most interesting part of Final Fantasy X’s combat, which is how so many of its core mechanics give the player more options on what to do in any given situation, adapt strategies on the fly and pull off maneuvers in ways that just weren’t possible in the previous three entries. Much like a lot of my favorite modern JRPGs, the mechanics introduced in FFX allows the game designers to set up almost puzzle-like situations that take time to think through and address properly

As stated before, that starts with the ability to change whichever weapons or armor each character is using at the cost of a short delay in their turn. This is big as it means individual characters can switch up their basic attacks to better approach the enemies in front of them, and make sure they’re properly protected against the type of attacks and status effects specific enemies will try to inflict.

It’s the kind of mechanic I had felt was really missing when I played through Final Fantasy VIII, which allowed players to equip elemental and status inflicting spells to their weapons and armor so they can inflict and resist enemy attacks that inflict the same. Unless you were using a guide to know exactly what was coming up, boss battles could be a wash the first time around and often I’d find myself automatically running from certain random battles because of my party’s set up. With the ability to switch up which spells were attached to attack or defense, that would never have been an issue.

But Final Fantasy X takes another step into letting the player switch up strategies on the fly because at any point, during a character’s turn, you can switch them out of battle with any other member of your party not in battle at the time. The first time I found I had the ability to do this, I almost thought I’d been given TOO much power. Not being able to switch out in battle felt like it was a base Final Fantasy mechanic, so what were they doing letting me change one character for another at will?

The answer is that they’d built the entire game around it. Even with the ability to change weapons, each character has limitations that keep them from being a good option against every enemy, and the key is that nearly every character added to your party in FFX is best equipped to take out certain enemies. Wakka is best equipped for handling flying enemies. Rikku can take out a machina enemy just by stealing from them. Faster ground enemies are easier for Tidus to hit. Certain enemies resist physical attacks and will need Lulu’s magic to defeat. And almost all of Auron’s weapons come with the Pierce ability, meaning he’ll do significantly more physical damage to armored enemies than any other character.

What’s more, FFX’s monster design very clearly demonstrates to the player when a monster fits one of these archetypes. Many of the same enemy types are used in different forms, yes, but certain enemy types are just obvious: flying enemies will be in the air and machina enemies look like robots and have a consistent design aesthetic. Armored enemies are clearly bulkier than others, fast enemies are thin and limber, and those resistant to magic often use magic themselves or look less physical in appearance. What’s more, the latter ones often have color schemes matching an element, giving the player an easy sense of which spell would be most effective.

One of my biggest criticism of PS1 and earlier era Final Fantasy games was that it was often almost impossible to tell whether what you were doing was working because it was effective or if it was just working due to brute force. The only way to do this was through the Scan spell, which could only be used on one enemy at a time and used up a turn. On top of all the other mechanics FFX introduced, one was making Scan an ability that could be equipped to a weapon, and was so for many early weapons the player obtains. This means that, while a character with scan is in battle, the player is able to view the enemy’s HP, and elemental weaknesses & resistances at all times. Put together, these abilities and mechanics essentially set up pieces of a puzzle for the player to decide how to maneuver the pieces at their disposal to solve.

As an example from an early boss battle, I switched out one character for another that could set up on opponent’s weaknesses, had the other two take out smaller enemies in the meantime before they could attack, and then switched the first character back in to take full advantage of the boss’s weakness. I often found myself counting turns in the game, targeting specific enemies knowing when they’d show up in the turn order to give myself more time, and switching characters in and out to provide set up and put them where I wanted in the turn order to achieve the best results.

Final Fantasy X made me feel smart for making use of its mechanics, even in the toughest of battles where I was barely scraping by, where previous entries made me feel like I was stumbling around in their systems, even in the best of scenarios.

But part of how this all fits together is also the biggest difference between the earlier PS1 titles and Final Fantasy X.

Defined Roles for Party Members

Part of what makes switching out party members on the fly work is that every member of the party has their own strengths and weaknesses that are different from other characters. They’re all different classes or jobs, a classic Final Fantasy system that didn’t make its way into the first two PS1 entries.

One of the reasons FF7 and FF8 didn’t necessarily need the ability to change out party members in battle despite only allowing for three characters in battle was how fluid those characters were. Any character could be equipped with any number of materia, including summons, and what had classically been considered white and black magic. This meant that basically every character could fulfill any of those classic roles. Certain characters were obviously better fit based on their stats, and players could maybe tell based on weapons and character design, but overall they could be anything.

It’s pretty easy to see why people like that system considering how much freedom it offers the player to build characters any way they want, but there are some issues. Giving the player so many choices can make the player unsure of which way characters should be built, especially if it isn’t immediately obvious.

Pulling away from classic Final Fantasy systems in FF7 and then doubling down in FF8, it makes sense why they reverted back to strictly defined classes in Final Fantasy IX. In accordance with this, they also increased the active party to four to make sure enough options were on the table in each battle. The benefit of having strictly defined roles like this is that it offers a sense of direction to the player from the get-go. They’ll know what the character can do, specifically, and how to make use of their abilities as best as possible.

The issue, then, with this more classic system is that the characters, as they are, are set in stone and party composition will require certain inclusions nearly every time. Since FF9 doesn’t let characters change classes or gain secondary classes, the game itself sees characters with built-in overlap to cover different bases. Nowhere is this clearer than between Garnet and Eiko, who are both able to Summon and also use White Magic, basically providing the player with two different White Mages.

Final Fantasy X, in some ways, manages to bridge the gap between the two titles in order to solve this issue, thanks to the Sphere Grid.

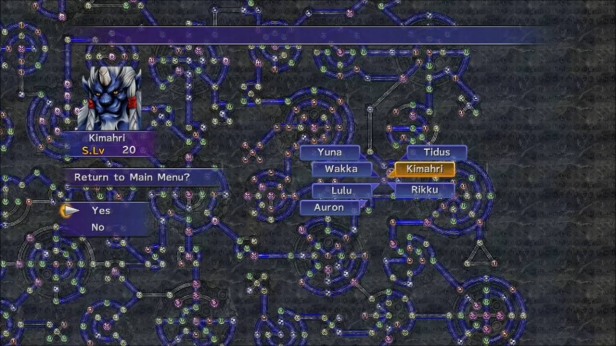

The Sphere grid is a huge interconnected grid of stat increases and abilities that the player slowly unlocks throughout the game instead of the classic system of leveling up. Every character is cordoned off into their own sections through locks that can only be opened with key spheres. Because the keys come in different forms, from level 1 to level 4, that are harder to find the higher level they are, often players will just move the characters through their regions of the sphere grid to unlock all the abilities that can be regarded as “theirs”.

But that being said, because of those key spheres, at any point, especially once a character’s region has been completed, each character will begin gaining stat increases and abilities that had been exclusive to a different character.

To me, this is the best of both worlds explored in the three PS1 entries. Characters have clearly delineated paths and abilities that make it easy for the player to understand what characters can do and how they can be used AND there’s clear customization available for each of them that lets the player build each of them in whatever way they see fit the further the game progresses.

By the time I fought the final boss, both the classic healer, Yuna, and the blue mage, Kimahri, both had access to the most powerful Black Magic spells, several of the physical attackers had access to Auron’s debuff moves, and even a few more had white magic that barely fit their job archetype.

The only character with no clear set path is that same blue mage, Kimahri. His area of the sphere grid is so small that the player will almost immediately run into locks, which is the intention because as the blue mage, Kimahri is an all-around type of character that is meant to spread out into all other’s areas. The design of his area of the sphere grid both forces this and also lets the player learn how the sphere grid operates and makes them start thinking about how they might want to grow not just Kimahri, but also the other party members.

It also means Kimahri is the one character that can be built from the ground up whichever way the player wants. He doesn’t have a base skillset, which puts him much more in line with FF7 and FF8 characters. The only differentiating factor between him and other party members ends up being that when he uses the Lancet skill, he gains Blue Magic for use on his “Overdrive”.

Which brings us to another battle mechanic through-line between these four games.

Final Fantasy’s Limit Gauge

Final Fantasy’s Limit Breaks work similarly to super meters, in that they slowly build up over time and let the character unleash a powerful attack or skill once full. They work essentially the same between FF7 and FF10, with the biggest change being that FF10 lets you choose from a variety of options as to how meter builds up. For most of the characters, it’s set to “taking damage” by default, but can be increased by inflicting damage, healing allies, killing enemies, winning battles or allies accomplishing something. Otherwise, there wasn’t much evolution in the mechanic between FF7 and FF10. If anything, there were mainly missteps that were merely reversed once FF10 came along.

FF8’s Limit Breaks aren’t bad per se, but they’re only accessible when a character’s crisis level rises, based on how low the character’s HP is, the number of other KO’d party members and how many status ailments they’re inflicted with. Essentially, this turns Limit Breaks into a last ditch effort ability that, while possible to manipulate by the player to use when they wish, are harder to come by. The quickest way around this is to cast the spell Aura on your team, greatly bumping up their crisis level and giving them access to their limit breaks immediately. However, doing so could very well make any enemy trivial.

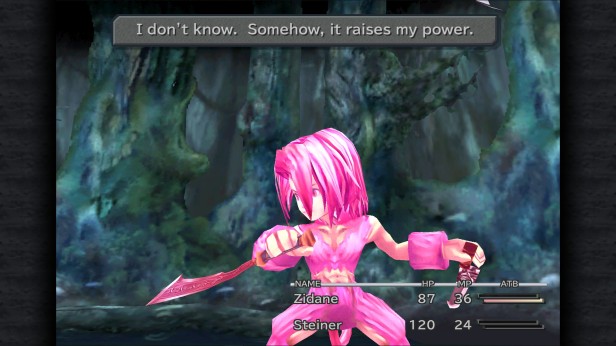

But the implementation I can, for sure, say just doesn’t work as well as it should, is the Trance system in Final Fantasy IX.

The Trance system takes its name from a similar form the character Terra had in Final Fantasy VI, where she transformed into a powerful state if she had enough Magic AP to use. FF9’s version functions more similarly to FF7, where a single gauge fills up over time, but instead of being a one-use move, puts the character into a Trance Form like Terra’s Esper form in FF6 that powers up the character until enough moves are used to deplete the gauge to zero.

There are two clear issues that alone could have worked, but together, ruin the system entirely. The first is that, due to the nature of the transformation lasting longer than a single move, the Trance gauge fills up extremely slowly, meaning the player will need to put in time and grind to have Trance form ready for a boss fight they might need it on. But that’s where the other issue comes into play: Trance Form activates automatically once the gauge fills up, and what’s worse, if the battle ends while in Trance Form, no matter how much meter is left, it will start empty on the next battle. Because of this, Trance is never something the player can plan on having and often can be lost on a random battle right before a boss fight.

Which is a shame, because it’s still a great idea as a concept and works itself into the story as well. When characters have emotional moments, they’ll start the battle off in Trance form, and it’s especially important to Zidane, who much more than the other characters, has a pink, furry, monkey-like form he gains when Trance activates. Though with that in mind, it is a bit strange that it isn’t a Zidane-only ability considering how it’s inspired by Trance in FF6, which was a Terra-only ability and, like in FF9, tied into her backstory and place in the world.

The Varied Implementations of Summons

Where Limit Breaks had their ups and downs when playing with different systems through these four titles, the developers seemed to find novel and interesting ways to implement summons in nearly every one of these entries.

Final Fantasy VII and Final Fantasy IX had the most classic approach, where Summons act, essentially, as fancy spells that cost more MP but can be spammed- at least for a limited number of times. But where FF9 took the classic approach of having certain characters take on the summoner job role, FF7’s freeform Materia system let any character cast a summon.

On the other end of the spectrum, Final Fantasy X decided to treat summons as their own character and really emphasized the scale of the creatures brought forth. When summoned, they’ll push the entire party to the background, leaving only themselves and the enemy in the field of play. They have their own health bar, special skills and can be taught common spells as well. The way they’re implemented makes them feel much more special than the grand, costly spell they are in other games. They’re also central to the story at large so you’ll also find yourself going up against them throughout the course of the story.

In the middle of these two implementations is Final Fantasy VIII’s summons, the Guardian Forces (GFs). Like FFX, they have broader implications than just being summoned, as they can be tied to a character using the Junction system to increase stats, resistances and attack elements. But in battle, they function almost the same as in FF7 and FF9, with two distinct differences. The first is that they no longer cost MP to summon, meaning, especially early in the game when the player doesn’t have a firm understanding of the Junction system, they’re very easy to spam.

What limits them is that summons don’t come out automatically. When a summon is selected, a gauge appears that slowly decreases. During that time, the summoner takes on the GF’s HP and is open to attack from the enemy. If the GF’s HP reaches zero, the summon is negated and the player won’t be able to call upon that GF until they’re healed. I find myself really liking this system as it emphasizes the time it takes for someone to cast a powerful summoning spell, even if the result is similar to past entries in the series.

But the GFs also represent the one battle system in these four entries that throws a wrench in my ability to appraise them together.

Final Fantasy VIII’s Wildcard of a Battle System

Final Fantasy VIII’s Junction system isn’t as complicated as it first may seem. The base concept is that spells can be attached to different stats (Atk, Def, Spd, etc.) to increase those stats, with stronger spells equating to larger increases. They can also be attached, if elemental spells or status inflicting/healing spells, to armor and weapons to inflict on enemies with basic attacks or offer characters resistances. The facet that determines if a spell can be attached or junctioned to a stat, armor or weapon is if the GF that is also junctioned to the character has the ability to allow it. It’s a very interesting system that I feel is the most cohesive of these four titles that, at worst, is necessary to avoid being outmatched by enemies that level up with you, and, at best, a lot of fun to play around with and find interesting combinations.

However, the other half of the system is what’s most controversial about it. Spells in FF8 are not abilities or commands that party members learn and have forever, and they do not cost MP to cast. Instead, they function essentially as ammo, specifically ammo that you can only acquire by draining (drawing) from enemies, who each house different spells. Each character can store up to 100 of any given spell and how much you store increases the spell’s effectiveness when junctioned to a stat, weapon or armor.

Naturally, that means the effectiveness of a junction decreases slightly every time a spell is cast, which is an interesting concept that makes the player choose whether spending spells is worth a decrease elsewhere. I found during my own playthrough that I’d much rather use other options than casting a junctioned spell, but even when I did, I also didn’t feel the slight decrease per spell to hurt my team’s strength over time. But if it were to, the player can also cast spells without spending their own stock by drawing them directly from the enemy they’re facing, giving yet another option to the player.

Unfortunately, the fatal flaw of the whole system revolves around the length of time it takes to build up a full stock of spells 100 times each. The draw skill, in my experience, averaged around 7 stocked spells per draw with a good Magic stat backing the command up. But that draw costs a turn and can only be used on one spell at a time, meaning to get a full suite of spells including Triple, Ultima, Flare, Meteor, etc. the player needs to grind for hours upon hours.

It’s not ideal, but since the system overall so cohesively works together- spells are drawn and stocked, GFs are junctioned to the player, then spells are junctioned to stats, weapons and armor- it’s easy to see how a turn-based structure would end up deciding that the player should have to gather those resources from enemies. So much of the battle system in FF8 is interesting and cool and fun, which is why it’s frustrating how many players were likely turned off to the whole game because of the need to grind to draw spells.

And while there aren’t many ways I can think of improving that area, there’s another key area that I feel can add a lot, and works directly in FF8’s favor. If there’s anything that FF8 can take from the games that came after it, it’s Final Fantasy X’s ability to switch weapons mid-battle. Specifically, I constantly felt like I was going into boss battles with the wrong spells junctioned to weapons and armor.

If a boss was inflicting my team with Zombie, Sleep or Petrify, I possessed no option to switch up what my party was resistant to, and if I couldn’t find a way to overcome it, would need to start again from an earlier point, set up the right junctions and go in again. It wasn’t as if I’d made a mistake before the battle, as there’s no way to know what a boss will do to you until a battle starts. Because of that, it makes little sense to essentially force the player to restart when they could just give the options to change those junctions mid-battle and let the player adjust on the fly. It’s a lesson that, despite its inclusion in FFX, Square Enix never seemed to learn, as the same issue exists in the recently released Final Fantasy VII Remake.

In Summary

It wasn’t a particularly hard call for me to say I preferred Final Fantasy X’s battle mechanics to the three PS1 entries that came before it. It already had a head-start by not using the ATB gauge and only strengthened that lead by reimplementing FF7’s Limit Breaks with added features, implementing the most interesting instance of summons, and struck a great balance between giving characters defined roles to guide the player before inevitably opening up the options to allow every character to be customized to the player’s liking.

On top of all this were the key changes allowing the player to both change weapons and armor mid-battle and even switch out a party member on their turn for another not in battle helped. Implementing them allowed the player to stop, strategize, move pieces around and set up devastating plays in ways that just did not feel possible in the previous three entries.

And while the main series continued to move on into an action-oriented direction with Final Fantasy XII, XIII, XV, and now the Final Fantasy VII Remake, Square Enix still has other teams putting out less financially successful titles that, still, develop these battle systems in new and interesting ways. It’s just that the competition has taken a step ahead, with Persona 5 selling millions of copies (twice).

But perhaps I should save talking about these newer turn-based battle system implementations for… another article.